How Trauma Affects the Body: Reflections from Dr. Eric Ball

How Trauma Affects the Body

Our four-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Everly, was recently killed.

Everly was an amazing dog and a true member of our family. She was well-trained and worked as a therapy dog at our local church. She especially liked the days when she would visit homeless or foster children. Everly slept in the same bed as our 12-year-old daughter. She was a great “big sister” to our 4-month-old puppy, who came to us just six weeks before Everly died. Most of all, Everly loved going on walks and “saying hello” to the neighborhood dogs. In a cruel twist of fate, she was killed on one of those walks.

It was a Saturday evening, just before dinner, and my wife took the two dogs out on our usual walking route. Halfway through, a large dog and his owner came walking toward them in the opposite direction. As they passed, the dog lunged forward and grabbed Everly by the head and neck and shook her violently. My wife witnessed the entire event and called for me and my son. I ran down the street to find Everly sitting in my wife’s lap wrapped in a kind neighbor’s blanket, paralyzed and gasping for breath. We quickly drove her to the emergency veterinarian, but she died in my arms on the way. I heard her last breath and felt her final heartbeat.

In the immediate aftermath, I could physically feel the adrenaline pumping through my veins. My heart rate increased and my breathing quickened. Even though I was preparing dinner at the time, I no longer felt hungry. My body and mind were fixated on helping my family and my “fight or flight” system had kicked in, big time.

I was suffering from trauma, and it was deeply affecting me, emotionally and physically.

Once we said our final goodbyes to Everly and returned home from the veterinary hospital, I noticed that my heart rate was still elevated. I was still “on edge.” I was still not hungry and could not sleep. The other dog was long gone and Everly was no longer with us, but my body and my mind maintained their ‘fight or flight’ posture. I was suffering from trauma, and it was deeply affecting me, emotionally and physically.

I hardly slept that night. My mind raced, and my heart fluttered. No matter how hard I tried, I was unable to settle down. I could still feel the adrenaline as I managed a few hours of restless sleep. When I woke up the next day, I continued to feel the effects of the trauma. They lessened with each passing hour, but anything that reminded me of Everly – an old photo, our puppy looking for her “sister,” seeing her favorite treat at the grocery store – would trigger another spike in my adrenaline.

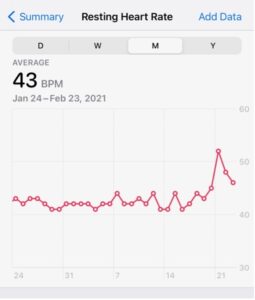

As a runner, I wear an Apple Watch to monitor my heart rate. I was shocked to find that my resting heart rate had risen by almost 25 percent on the day of the attack and stayed elevated for the following two days. Forty-eight hours after the trauma, my body was still ready to fight (see figure 1). I also felt the stress response in other aspects of my life. I hardly ate for two days and lost five pounds. I continued to struggle with my sleep (see figure 2). I found my mind wandering during conversations and settling in a dark place where my dog is being killed.

Figure 1. My resting heart rate over time. Attack occurred on February 20.

This is how trauma affected my body, emotionally and physically. The experience led to a short-term increase in my stress hormones, raising my heart rate, depriving me of sleep, and taking away my drive to eat. Short-term, this is a good evolutionary strategy because it allows a person to focus resources on fighting or escaping impending harm. But long-term, and unchecked, this is deadly because this stress response causes an evolution in hormones that, over time, leads to inflammation, wear and tear on the body, and higher risk to many physical health conditions.

Things are gradually improving. The day after the attack, our home was flooded with flowers, cookies, and other treats as our support system kicked in. We were visited by a steady stream of family and friends who sat with us in the backyard, remaining physically distant, as we all reflected on Everly’s life. Talking about the event helped.

I also started using the techniques that I have learned from my ACEs Aware training to build resiliency in myself and my family. I made sure to exercise the next day. Although I was exhausted from not sleeping, going for a run helped to clear my mind and made it easier to sleep. I forced myself to eat healthy food, even though my ‘”fight or flight” body was not hungry. I pulled out my phone and meditated, using my favorite meditation app. My wife and I even chatted with our good friend, a psychiatrist, for an informal backyard therapy session.

My family will be okay. My heart rate continues to normalize, and I can feel a calm returning to my body. I am lucky. I have a loving family and a great group of supportive friends, another dog with whom to snuggle, and immediate access to mental health care.

I do not want to minimize the loss of Everly to my family, but if this is the body’s reaction to the traumatic loss of a pet, imagine what one would feel over the sudden loss of a human loved one. Imagine the effects on the body of living in an abusive or neglectful household or one in which a parent or caregiver is incarcerated. Now also imagine that this trauma is continual or long-lasting. Further, imagine that the victim does not benefit from the resiliency factors I have.

For these children, the changes that I felt in my body for days will last for weeks, months, or years.

This is toxic stress, when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship —without adequate adult support. For these children, the changes that I felt in my body for days will last for weeks, months, or years. The high levels of stress hormones can, when unchecked, lead to dramatically higher rates of psychological and physical conditions over time.

In California, providers are collaborating with the ACEs Aware initiative to screen and treat children and adults with histories of trauma. We are conducting annual screenings so we can identify children at highest risk for the health effects of toxic stress. Once identified, we are working with these families on building resiliency and getting them mental health support, if needed. Our goal is to reduce the effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) by half in one generation. Although we may never fully eliminate childhood adversity, we can identify and help the children who experience it.

Our family is doing better, and our puppy is adjusting to her new life as an “only child.” Thanks to the techniques we learned through the ACEs Aware initiative, my wife, children, and I are using stress-busting techniques to help regulate our stress response to get through these difficult times. It is our sincere wish that all children have the same opportunity to live safe and healthy lives, free of stress and adversity. Through ACEs Aware, we can make this happen.